Publication 4 of 2026

Imbolg – St. Brigid’s Day – Lá Fhéile Bríde – 1 February

‘Anois teacht an earraigh, Beidh an lá ag dul chun síneadh, ‘S tar éis na Féile Bríde, Ardóidh mé mo sheol.’

– Antaine Raiftearaí (1779 – 1835)

Introduction

The St. Brigid’s cross has been made, and homes were cleaned in preparation for her arrival, ribbons or strips of cloth tied to the sceach outside. Since 2023, Ireland has a Public Holiday to mark St. Brigid’s Day and Imbolg. Imbolg is one of the four main ancient Gaelic festivals: Samhain, Imbolg, Bealtaine and Lúnasa, all of which now have a corresponding Public Holiday. There is an enormous amount of history, tradition and heritage associated with this time of year, so here’s just a taste of that…

Imbolg: A Whisper of Light & Heat to Come

Imbolc signals the time the Cailleach may yield to Brigid, and from wizened spindly fingers, relinquish her wintery hold on the land. Depending on the depth of the winter, the first early signs of spring flora may emerge. Buds are visible on the trees. Daylight has noticeably lengthened since an Nollaig, and Irish people comment on “A grand stretch in the evenings”. Birdsong has become more audible. Cattle and sheep are gestating and there is a promise that all of nature – life itself – will flourish again soon.

Imbolg: What does it mean?

The origins or possible evolution of the word imbolg is not 100% certain, but there are theories. Some believe it comes from Old Irish i mbolc ‘in the belly’, and reflects the pregnancy of cattle and sheep. This is certainly how I have understood it, but this may not be correct. Another idea is that it may come from imb-fholc suggesting a ritual of washing or cleansing. ‘Ewe’s milk’ seems to be the interpretation from an early historical term associated with the festival, Óimelc. This term is over 1,000 years old. More on this below.

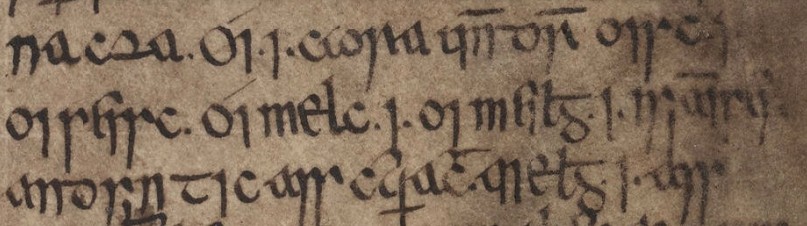

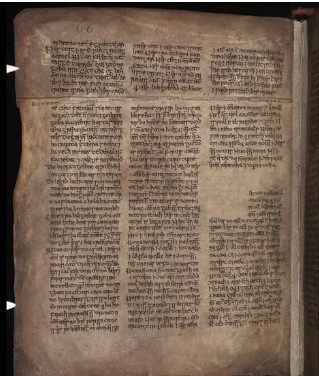

Imbolg appears in one of the oldest dictionaries in Europe!

Early written references to the festival go back to Sanas Cormaic, ‘Cormac’s Glossary’. The earliest version of this collection of over 1,400 arcane words has been attributed to Cormac mac Cuilennáin, a Bishop and King of Munster, killed in battle in AD 902. Cormac’s Glossary is written in the vernacular (the plain language of the people) and is possibly the first such dictionary ever written in Europe in any of the non-classical languages. [Remember, for centuries, colonial propagandists said Gaelic culture was in need of civilisation. In fact, Ireland was a beacon and bastion of education during the Dark Ages, and education tourism flourished – but I digress.] Imbolg or something corresponding to it appears in Cormac’s Glossary as Óimelc, ‘Ewe’s milk’.

Brigid, Brigit or Bríd…

Brigid, Brigit, Bríd, Bridget and Brighid are all names associated with the female figures celebrated at the commencement of February. There is the Goddess Brigid, the Saint Brigid, and the Brigid who overlaps both. Brigid can transcend many things including beliefs and she represents different things to different people. It was Irish Christians that first started to write down Irish mythology and folkore. The subsequent history of a patriarchal society was recorded predominantly by males and about males. Brigid, in her various forms, represents something of a rebalancing. For many, she is a feminist icon.

Brigid, Pagan Goddess

As with the age of Imbolg, it is currently impossible to say how far back worship of Brigid goes. 2,000 years would probably be a conservative estimate. We know that the time of year that Brigid is celebrated corresponded with something that goes back 5,000 years in Ireland. At the sacred Hill of Tara, the Neolithic passage tomb known as the Mound of the Hostages was constructed and aligned to be illuminated by a shaft of light from the rising sun at Imbolc and Samhain. When we mark this time of the year, we do so in the knowledge that this tradition is shared with people who lived in the Neolithic period (New Stone Age); the pre-Christian Pagan Gaelic population; the Christian Gaels; and for many others from different backgrounds who have lived here. Many of our schools do a good job of ensuring the continuation of these traditions, in an inclusive manner.

Brigid was obviously a powerful Goddess in Pagan, pre-Christian Ireland. ‘Brigit’, as she’s referred to in Sanas Cormaic, the deity, was the daughter of The Dagda, who was the chief God of the supernatural race, the Tuatha Dé Danann. Brigit had two sisters, also called Brigit: one a healer, the other a smith. Some have interpreted this as Brigit having been a triple deity. Brigit was said to be adored by poets, a protector, having great respect and influence, and sage-like wisdom. In a marriage of political alliance, intended to create peace between the warring Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians, she married Bres, who was half Fomorian. They had a son, Rúadán.

Keening

When Rúadán is killed in battle, Brigid is reputed to have invented the Irish tradition of keening. Keening is a sung lament for the dead. Keening (from the Irish ‘caoin’, to cry or mourn) involves the singer, usually a woman, performing a ritual song and fluctuating between notes while singing the same syllable of word [a melisma?]. Some perceive the influence of keening in the styles of two of Ireland’s great singers, Sinéad Ó Connor and Dolores O’Riordan. Brigid is also credited with the invention of a whistle for use in night travel.

Saint Brigid

Naomh Bríd (St. Brigid) or Brigid of Kildare, the historical figure, is reputed to have been born half way through the 5th century, and lived for about 75 years. She is one of the three National Saints, along with St. Patrick and St. Colmcille. Born into slavery and eventually freed, Brigid grew up with farm work. Brigid refused to marry and pursued a spiritual life, often tending to the poor. At some time around 480AD, she is credited with founding monasteries in Kildare, and becoming the first Abbess of Kildare.

Probably the best known of the stories about Brigid involves her asking the King of Leinster for land to build a convent. When he refuses, she invokes the power of God. She asks if the King will grant her the amount of land that her cloak will cover. The King, finding this amusing, agrees. Miraculously, Brigid’s cloak expands to cover the area of the Curragh in Co. Kildare. The King is cowed, converts to Christianity, and agrees to give Brigid the land she wants.

Legacy

It is still a habit for many families – or children attending primary schools – in Ireland to continue the celebration of Brigid. The most common tradition is probably the making of the St. Brigid’s Cross. These crosses used to be put up in the home for a year, and were burned when it was time to create new ones. Another tradition is the making of the Brídeog doll. There are some photographs of different forms of the St. Brigid’s Cross and the Brídeog, below.

One way to estimate the impact and legacy of Brigid is to see the number of placenames and holy wells she is associated with. There are places called Kilbride all over Ireland – Kilbride is a manglicisation of the Irish placename, Cill Bhríde (The Church of Brigid). There are at least 68 Kilbrides recorded on the Irish placename database, logainm.ie, not including other variations. On the Dúchas.ie website (of the National Folklore Collection) versions of her name appear thousands of times – both in English and in Irish.

Conclusion

I will conclude with a simple quote from a child who contributed to the National Folklore Schools Collection in the 1930s, Máire Ní Dhonnabháin, Co. Waterford. In this quote we see continued associations with Brigid and kindness, caring for the poor, and providing them with sustenance – a noble concept 1,500 years ago, and still today, “Bhí Naomh Bríd an-mhaith dos na daoine bochta. Bhíodh sí ag déanamh im.” (‘Saint Brigid was very good to the poor. She used to make butter.’)

Happy St. Brigid’s Day/Imbolg to all!

If you enjoyed this article on the origins and traditions associated with St. Brigid’s Day and Imbolg, please share it on social media, or follow me on social media: IrishLanguageMatters on Instagram and Threads, @derekholly7.bsky.social on Bluesky, @DerekHolly7 on X. Go raibh maith agat!

You can help fund the work I do by supporting me on Patreon with the price of a coffee every month.

You can help fund the posts and articles I do here by supporting me on Patreon with the price of a coffee every month.

3 sisters all called Brigid. That must have caused some confusion.

I enjoyed that. It was a very interesting read.

LikeLiked by 1 person