‘They had the mantra “That was never a real language!”’

The Manx language has seen a remarkable turnaround. When the 97-year-old Ned Maddrell died in December 1974, the last native speaker of the Manx language had passed. In 2009 UNESCO declared Manx an extinct language.

It is of interest in Ireland because the Manx language is a Gaelic language that is closely related to Irish. An Irish government was involved in making efforts to ensure Manx did not disappear. Furthermore, there may also be lessons to be learned in terms of language revival and revitalisation as, like Irish, Manx battles to find breathing space within the Anglosphere.

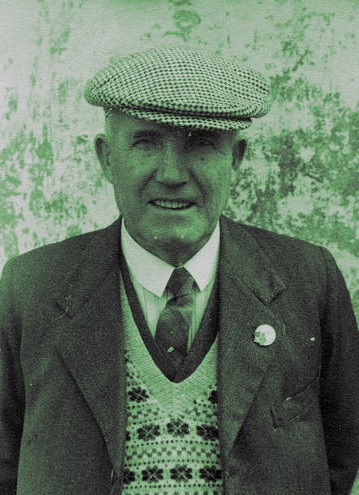

Brian Stowell’s (1936-2019) name is synonymous with the revival of the Manx language. He is credited with being a principal driver of the regrowth of the Manx language in the Isle of Man. With a background in Physics and academia, Stowell learned and taught the Irish language in Liverpool where he lived for some years. He returned to the Isle of Man permanently in the 1990s. Brian had strong opinions about what worked and what didn’t in terms of language restoration. I was fortunate to have had contact with Brian in 2015 and the quotes below are taken verbatim from that correspondence.

The Early Manx Language

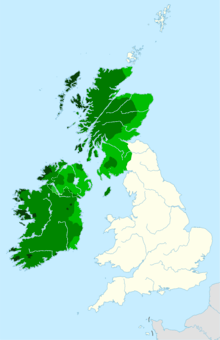

There are several large stones inscribed with the Ogham script located on the Isle of Man. This is the ancient written form of what is termed ‘Primitive Irish’, the earliest form of the Irish language in the historical period. These Ogham stones attest to the presence of Primitive Irish in the Isle of Man from around the 4th century, possibly carried by missionaries, migration or seafarers. At around this time, the Irish language also spread to Scotland. The Manx Gaelic language is therefore a sister language of Irish and Scots Gaelic – all are descended from Primitive Irish and then Old Irish. About a thousand years ago, Irish was spoken across all of Ireland, almost all of Scotland and the Isle of Man, apparently also with settlements of Gaelic speakers in Wales and England. Over time, the languages diverged and Manx evolved. Spoken Irish and Manx are partially mutually intelligible to this day. However, the Manx orthography, or spelling system, is quite different from that of Irish or Scots Gaelic.

Decline and Preservation Efforts

Manx was the primary spoken language of the Isle of Man for many centuries as outside influences came and went, or were assimilated: Irish and Scottish Gaels, Christian missionaries carrying the Latin language, Norse-speaking Vikings and the English. Traditionally, the Isle of Man had close connections with the Gaelic-speaking populations living on the coasts of Ireland and Scotland. As the Gaelic languages in Ulster, Leinster and Galloway declined due to various forces – mostly the direct or indirect result of colonialism – the Isle of Man became geographically cut-off from the other Gaelic speaking peoples. From the 17th – 19th centuries, English became the medium of education and this contributed to a decline in usage of Manx. From the late 19th century, the level of usage dropped dramatically until, by the 1920s, only about 1% of the population spoke Manx.

There were also some similarities with the situation in Ireland. English was the language of education and administration and started to be perceived as a superior language – a more useful language – and negative attitudes developed towards Manx. This is a common occurrence with minority languages and highlights the importance of positive attitudes. There was severe poverty in the Isle of Man in the mid-19th century and the language became associated with this impoverishment. ‘A common saying among the old Manx speakers was ‘Cha jean oo cosney ping lesh y Ghailck’, meaning: “You will not earn a penny with Manx.”’* Many parents opted not to speak Manx with their own children – effectively preventing them from learning the language.

In 1947, Taoiseach Éamon de Valera visited the Isle of Man and met several of the last remaining original native speakers of the Manx language, including Ned Maddrell. De Valera spoke in Irish Gaelic, Maddrell in Manx Gaelic. Following this visit, he sent the Irish Folklore Commission to the Isle of Man to make recordings of the native speakers in an effort to help to preserve the Manx language. By this time, only a handful of older speakers remained and the last one, Ned Maddrell, died in 1974. Manx was declared extinct by UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages Under Threat in 2009 (subsequently reclassified), but long before this, a cultural revival had begun, centred around the Manx language and identity. Brian Stowell is credited as having played a leading role in this revival. He learned Manx and made recordings of Ned Maddrell speaking the language in the 1960s. You can listen to a 1964 conversation between the two men on YouTube.

Attitudes to the Manx language

Over a decade ago Brian Stowell appeared on Manchán Magan’s TG4 television show ‘No Béarla’ (No English). He stated that the dying off of a generation of Manx people who were mostly opposed to the language cleared the way for a psychological reset. Brian said that, about 50 years before, many older Manx people would react angrily to people learning the language saying things like ‘That was never a real language!’ In those days the last native speakers were also old and were convinced that the language was dying.

According to Stowell, the National Curriculum for education brought over from England was disastrous. He thought the idea of having a compulsory language subject at school was counterproductive, and very foolish. He suggested that in such a cohort, the prevailing attitude will be that children will have absolutely no interest in the language. He suggested that if the choice is left up to children, they will choose the language and they will be committed to it.

In 2015, Stowell told me:

‘My making slightly flippant figures [remarks] about old Manx people dying had nothing at all to with old native speakers dying. I was referring to the apparently large numbers of older Manx people who were very strongly (viscerally!) against the language. The dying off of such people (they had the mantra ‘That was never a real language!’) probably was a factor in the very real change of attitude to Manx – it’s generally very positive’.

He said the attitudes of the last known original speakers were sometimes more positive:

‘The known surviving Manx native speakers were all very keen to pass on their Manx – the prize one being Ned Maddrell. Heaven knows how many people there were who never revealed they were native speakers. It’s well known in some countries that quite a few native speakers don’t want to pass on their language and are irritated by revivalists’.

The Revival

There had been a cohort of Manx citizens learning Manx as a second language going back some time. Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh (the Manx Language Society) was founded in 1899 in a move mirroring the establishment of Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) in Ireland, in 1893. The organisation’s motto is ‘Gyn çhengey, gyn çheer’ (Without a language, no country) which also has a parallel in Ireland with ‘Ní tír gan teanga’ (No nation without a language).

In 1992 Manx was offered as a language option in schools on the Isle of Man. Brian told me:

‘For all the primary schools about 40% of children over 7 wanted to study Manx – the figure was between 6 and 9% in the secondary schools. This was all with parental approval. We were stunned by these figures and couldn’t cope with the demand with the resources allocated. At present, about 1,000 children study Manx as an option. Bunscoill Ghaelgagh started in 2002’.

I asked Brian how he would you rate the progress of the Manx revival movement, and what percentage of Manx children were being educated at Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, which is the Manx-language-medium primary school. Here, the children are educated entirely through the Manx language. He told me:

‘Compared with the desperate situation up till about 30, 40 years ago, Manx Gaelic has made phenomenal progress – that was from a very low base. No one in the quite recent past would have dreamed that there would ever be a school where the teaching was though Manx. There are about 50 children (say) at Bunscoill Ghaelgagh. Saying there are about 10,000 children of school age in the Isle of Man, the figure you’re asking for would be of the order of 0.5%. This looks ridiculously low but you have to remember the situation we are getting out of.’

He added: ‘Anyway we don’t too get tied up with percentage figures as they seem to be in Scotland concerning Scottish Gaelic.’

The Isle of Man now has a few families raising their children with Manx as their main spoken language. There are also up to 2,000 second language speakers of varying abilities. There are currently 53 children receiving their primary education entirely through Manx. As with Irish, technology is making it easier for learners to access the language through social media, apps and online resources. This also makes it possible to connect with speakers and learners that might not meet otherwise.

‘Brian [Stowell] was an inspiration to us all,’ says Julie Matthews, Head Teacher at Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, where one of the former pupils is now back at the school as an Education Support Officer. Matthews says:

‘The language revival is certainly going strong. There are many adults now learning and it’s great to see as a result of sending their child to the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, many parents have taken up the opportunity to learn Manx too and are welcomed into the language speaking community. There are many more informal chat sessions popping up around the place and it’s great to see the young ones taking a pride in their language and joining in or setting up their own groups’.

Conclusion

To those unaware of the issue of language shift and cultural struggles for survival, the story of Manx may seem insignificant because it has not come remotely close to displacing English as the vernacular – and maybe it never will. However, to observe any minority culture from the viewpoint of a dominant culture would be a false perspective. Most of the world does not speak English. Most of the population of the world is bilingual or multilingual. Most humans belong to cultures which are under some threat.

The story of Manx is particularly remarkable because the Manx language lives on and grows after it lost all of its native community of speakers. Its existence enriches and enhances the Manx people’s culture and sense of identity alike. The story of the revival of the Manx language can inspire speakers of minority languages, particularly speakers of the Irish language.

At the heart of all successful movements are people like Brian Stowell. He, still missed and spoken of fondly, is a role model for many, and he provides evidence that one person can set an example, and make a difference. Brian’s passion and example suggest that we can all challenge ourselves to take personal responsibility for our own cultures, and our languages.

Potential Lessons for Irish:

- In local areas, language shift can occur relatively quickly. Ned Maddrell grew up in Cregneash where, in the 1870s & 1880s, Manx was essential. By the time he died, he was the last native speaker on the whole island

- Like Manx, the Irish language can lose its community of speakers

- Attitudes towards languages definitely have an impact on language usage

- As with Manx speakers, it is likely there will always be people who will identify with Irish as their language, and will ensure it survives in some context

- Languages can be revived and revitalised

- Irish has a relatively broad base on which to achieve revitalisation

*Quote from an article in The Guardian by Sarah Whitehead, 02/04/2015. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/apr/02/how-manx-language-came-back-from-dead-isle-of-man

Brian Stowell died on 18th January 2019.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam

-Article by Derek Hollingsworth, February 2022

Thanks to Julie Matthews of Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, Chris Sheard of Yn Çheshaght Ghailckagh, Vincent Dillon & Paddy Seery (Dublin).

Gura mie mooar eu! (Manx Gaelic)

Go raibh míle maith agaibh! (Irish)

Follow Me

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.