New York, New York, so good they renamed it several times…

Introduction

New York City is one of the world’s most iconic cities. From its multiple famous landmarks to the innumerable movies set in ‘The Big Apple’, it is a city that many feel a connection with. As of 2022, 8.85 million people call New York City home. It is impossible to be in their midst and not feel like a minor character on an over-sized film set. New York is the City of Billy Holiday and Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle. It is associated with characters as diverse as Al Capone and Bob Dylan. It is a city of culture and capitalism, and home to Greenwich Village, Broad Way and Wall Street.

The Irish Connection

There have been many Irish connections with New York City including Irish mayors, bishops and gangsters – occasionally not mutually exclusive roles. Several million Irish migrants have relocated to the US since the 17th century. Of these, 3.5 million Irish passed through Ellis Island Immigration Station in the 62 years it operated; its first migrant being 17-year-old Annie Moore from Cork.

Historically, there was a significant Irish population in the 19th century Five Points neighbourhood of Lower Manhattan. This was the notorious simmering swarm of a melting pot where the mix of Irish and African-American cultures produced tap dance and a music hall precursor to jazz and rock & roll music.

The Irish language in New York

Many of the migrants from Ireland were Irish-speaking and some of these were monoglots – Irish was their sole language. Some of these Irish-speakers settled in New York and some further afield. The poet Pádraig Phiarais Cúndún emigrated in 1826 settling in Deerfield, New York. He died in 1856 having never learned English, being surrounded by a community of Irish-speakers in the area.

Many Irish had their names Anglicised; this happened for a variety of reasons including that some migrants wished to fit more seamlessly into a predominantly English-speaking culture. It has been suggested that many international immigrants changed their names within 5 years of arrival, and lost their languages within 3 generations.

Having said that, today there is an Irish-speaking community in New York. People socialise through Irish, and entertainment and events are organised at various locations including Lehman College and with Daltaí na Gaeilge. There are two branches of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaeil Nua-Eabhrac and Cumann Uí Chléirigh in Brooklyn) and Irish language classes are available at Glucksman Ireland House, the Irish Arts Centre, Lehman College and several other locations.

Language and Memory

Post-colonial theorist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has often outlined how colonial powers always attempt to impose their language on the dominated. He suggests that this is partly due to language being a carrier of memory. He has spoken about travelling through the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, birthplace of great African leaders such as Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko. Here he found towns with names such as King WillIam’s Town (renamed Qonce in 2021), Queenstown, Frank Fort and Berlin – town names bereft of any African identity. He suggests the native names, memories and histories have been buried under a European memory as a result. It is interesting to consider New York City from this perspective.

New York and its changing identities

New York has an illustrious name among the cities of the world. It and its people have had multiple and evolving identities during its history. Under its current name and identities lie former names, identities and histories, some of which are now forgotten or somewhat hidden beneath the layers. One of the lesser known stories of New York, at least in Ireland, is the story of its name changes. These name changes sought to create new identities for the place that is now the famous cosmopolitan city of 800 languages.

New York named by the English in 1664

The English seized the City from the Dutch in 1664 and renamed it New York in honour of the then Duke of York, who would go on to be King James II. (Following the manner in which he fled Ireland after the Battle of the Boyne, James II was held in contempt by his Irish followers and nicknamed Séamus an chaca, ‘James the shit’, in the Irish language.)

The Kingdom of Great Britain was subsequently formed in 1707 when England and Scotland merged. New York was one of the Thirteen Colonies that made the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776, separating from Britain.

Manhattoe/New Amsterdam 1625-1664

Before it was known as New York, an area at the southern end of Manhattan Island was called New Amsterdam by the European settlers living there. New Amsterdam was the administrative centre for New Netherland, a 17th century colony of the Dutch Republic on the east coast of America. The Dutch began settlement from 1624 and a fort was built, Fort Amsterdam (possibly by exploiting African slave labour). In 1653 New Amsterdam received municipal rights and officially became a city.

During this period, the upper three-quarters of Manhattan Island today were a hunting ground for the Wecquaesgeek people, who became extinct in the 17th century. They were a band of the Wappinger Native American people who, unfortunately, also subsequently became extinct – their interactions with Europeans led to their decline and extinction as a tribe by the early 19th century. Native Americans had been living in the area around the Hudson River (named for an Englishman working for the Dutch East India Company) for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. The natives called the area at the southern end of the island Manhattoe, a word adopted by the Dutch and English.

La Nouvelle – Angoulême (1524)

Earlier still, the Italian explorer Giovanni de Verrazzano arrived in the area in 1524 and was met by local natives in canoes, members of the Lenape people. De Verrazzano gave the area the name La Nouvelle – Angoulême in honour of the French King who was the patron of his expedition and had previously been Count of Angoulême in southwestern France.

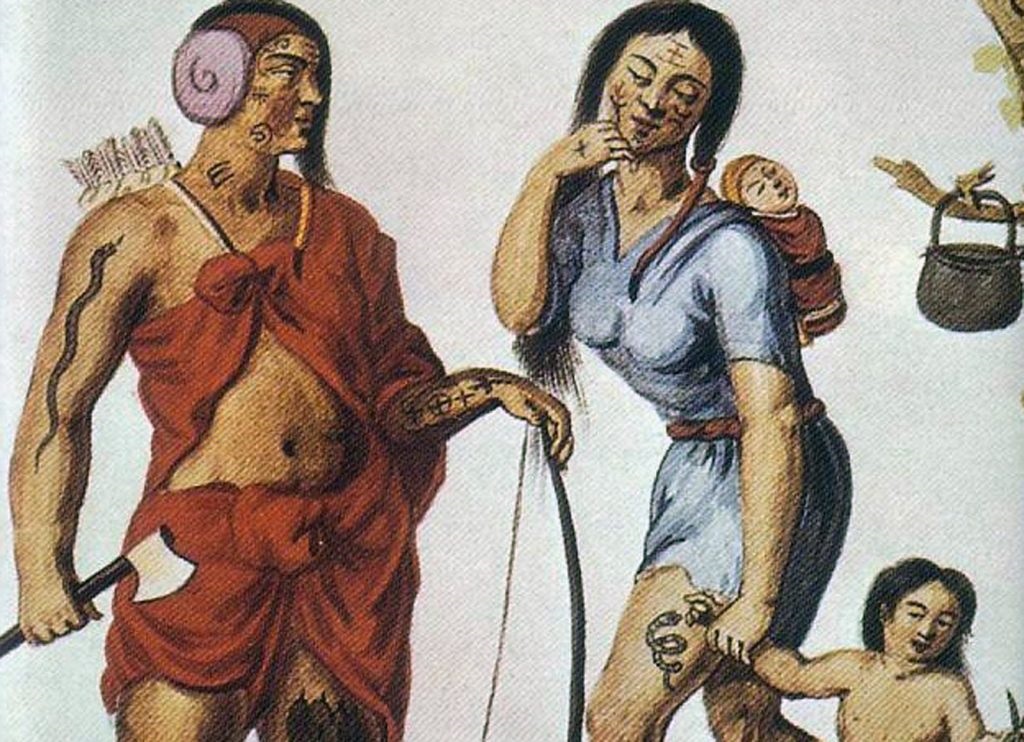

The Lenape People or Lenni-Lenape (original people)

At the time of first known contact between the Native Americans and Europeans, the Lenape people were known to be in the modern New York area. Their farming and fishing methods supported up to 15,000 people in scores of settlements in the New York City area. The Lenape spoke two closely-related dialects, Munsee and Unami; these Lenape languages belong to the Algonquian language group. Some of the local names included Hackensack (Upper New York Bay), Canarsee (Long Island) and Raritan (New Jersey and Staten Island).

Due to the encroachments of Europeans, and subsequently the United States, the Lenape were gradually displaced from their aboriginal lands. As a result of this process of displacement, many of the remaining Lenape people now reside in Oklahoma, Wisconsin and Ontario. It is estimated that there are about 16,000 Lenape people today.

Sadly, the Lenape languages have fared even worse. The Munsee language had only two native speakers left as of 2018, aged 77 and 90. Some younger people are making efforts to learn the language. The last remaining speaker of the Unami language died in 2002 – that language is now extinct.

What’s in a name?

It would be ridiculous to suggest that a place name alone could define a place, especially one as diverse as New York City, with nearly 9 million people – about 1% of whom are Native Americans – and over 800 languages. Nor can a place name ever encapsulate the full history of an area. That said, New York illustrates how the naming of a place certainly has a role in the memory and ownership of that location. New York is just another example of the colonial practice of replacing native names. This practice necessarily involved foisting a new memory and identity onto what was there before – the replacement of people, history, culture and language.

Native place names are important capsules of history and culture. ‘Denali’ suggests a totally different narrative to ‘Mount McKinley’, ‘Uluru’ tells a different story to ‘Ayers Rock’. Today, when we conceptualise New York City, does the Native American even enter the frame?

-Article by Derek Hollingsworth, February 2022

Thanks to Jeff Davy (Warsaw), Ed McSweeney, Vinnie Dillon (both Dublin) and Caoimhe Nic Giollarnáith (New York)