Publication 2 of 2026

“Oíche Gaoithe Móire, Óiche stoirme’s dóite” – Michael Burke

(“It was a night of great wind, A night of storm and burning”)

Oíche na Gaoithe Móire, (the Night of the Big Wind), Sunday, 6 January 1839. Possibly the worst natural disaster in Irish history, it has been ingrained in folk memory.

A chairde, Athbhliain faoi mhaise daoibh! I hope everyone had a happy, healthy and peaceful Christmas. This is my first piece of 2026, and I hope it resonates with people who are interested in Irish history and culture.

6 January is the anniversary of Oíche na Gaoithe Móire, when earth, wind, fire & water tormented Ireland. I’ll describe some of what was reported about this incredibly violent storm, and discuss where it fits in to the wider language issue in Ireland. I’d love to do this one as a podcast. Hold on to your roof!

The Calm Before the Storm

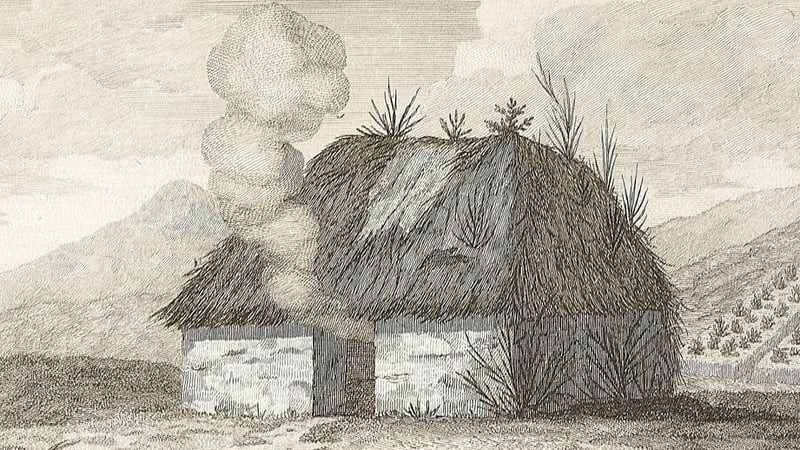

Late on Saturday, January 5, 1839, there was a heavy snowfall in Ireland. It is unlikely that any but the children of the well-off were able to make snowmen the next morning. There were huge swathes of the rural peasant class living in poverty. Families existed in small thatched and mud-based cottages. The majority of the children in these communities would not have had shoes. Irish was the dominant community language of Munster and Connacht, with English having become the majority language nationally only in the recent past. Almost all the ingredients were already present for catastrophic population and language collapse. But that was still a few years away.

The Storm. Sunday, January 6, 1839

The following day, the day of the storm, saw a full thaw and warm, still conditions that have been described as eerie. Thick cloud overhead sealed in the motionless air below. The warm front was about to be met by a rapidly moving Atlantic depression. The West of the island felt the approaching energy first. By early evening the winds had been roused, and a hellish experience was about to be unleashed. Hurricane force winds haunted the land in the darkness. A storm surge brought huge volumes of water inland causing floods. Extraordinary things were witnessed. The water was almost totally blown out of the canals in Kilbeggan and Tuam. Waves were said to have topped the 702 ft Cliffs of Moher in the Burren. Thatch from rooves was blown in to fires throughout. In Kilbeggan fire spread to 12 houses in an hour, consuming all. Panic ensued as people fled their collapsing dwellings. In the West there were many reports that people were unable to stand, and had to crawl to save themselves or to assist children or neighbours. Some parents tried to secure children in containers for fear they would be blown away. Windows were blown in. Fires raged. At sea, it was apocalyptic. Over 6 January, and the subsequent days, there were many ships wrecked and sunken around Ireland and Britain. Finally, less than 12 hours after the winds got up, the storm released its grip on Ireland.

Destruction and Legacy

The Night of the Big Wind must have been a truly terrifying experience for the population. There had been a folk belief that the the world would end on the 6 January, and some must have believed that was unfolding. Others attributed the violence of the night to the activities or anger of the the fairies. 100 years later, the term ‘Oíche na Gaoithe Móire’ appears 68 times in the 1930s Schools Collection of folklore, and ‘Night of the Big Wind’ occurs 97 times.

There was massive destruction wrought on nature and wildlife. Food and supplies were depleted. Tens of thousands of structures were damaged and the estimates are that 250 – 500 people lost their lives, though this is likely to be underreported. Factories, churches and barracks were damaged or destroyed. Crops were lost leading to the starvation of livestock and food shortages for the poor.

Tragically, the depletion of resources was so great that the storm worsened the Famine, years later. Entire villages and shipping fleets had been destroyed. Hundreds of sea vessels were sunk or battered, and millions of trees had been felled in the gales of that January night. Poor, rural, Irish-speaking communities were weakened and could not recover before the next calamity.

On the Night of the Big Wind, people were crushed under the stone of their own homes, assaulted by the winds, burned by fire and drowned in water. Thousands of homes were destroyed. The hurricane left an unforgettable mark in folk memory.

Conclusion: The Impact on the Irish Psyche and the Language

I’m really interested in the psychology of the language shift – the process by which the dominant community language changed from Irish to English. I think the subject is really fascinating, and I’m sure that understanding these processes better can give us insights into what can be done to preserve and grow the Irish language, and to mature and decolonise as a society.

Think about the cumulative psychological impact on the Gaelic population of the following in terms of how the Irish language went from a source of pride to a badge of shame:

- the savage civilian slaughter and scorched-earth policies of the English colonialists in the Desmond Rebellions (1569 – 1583)

- the completion of the English colonial Conquest of Ireland (finally completed after 400 years in 1603 following the Nine Years War)

- Cromwell’s genocidal depopulation of Ireland (1649 – 1653) and “To Hell or Connacht” (meaning the dispossessed population could face slaughter or leave their lands for the unforgiving rocky soils in the West. Relocated there, on meagre plots with poor land as tenants, and engaged in subsistence farming, there was only one crop that would produce enough food to feed a family…

- Oíche na Gaoithe Móire (1839) took place on the Feast of the Epiphany, at a time when some Irish people believed the world would end on a 6 January. There was a growing religiosity among the subjugated Gael, though not to the extent of the religious extremists who oppressed them

- An Drochshaol/The Great Famine (1845 – 1852) [A couple of people on social media have asked was this not Ireland’s worst natural disaster. My answer to that is that the blight was a natural event, but the colonial processes before, during, and after the blight were what made it a disaster. So, no.]

When we reflect on the horrific sequence of events above we can begin to understand the shame that is still associated with the Irish language today. (Listen to Síle Seoige speak with her guest, Doireann Ní Ghlacáin, in ‘The Cailleach’ on her ‘Ready to be Real’ podcast. We feel shame if we speak Irish, and we feel shame if we don’t speak Irish well enough. We need to cast off this shroud of shame, and embrace the shimmering beauty we still have in our language, our culture, the music in so many genres – like a coat of many colours – and our amazing storytelling traditions. The creativity comes bursting out of us.

The Irish speaking community eventually came to associate ignorance, poverty, death and emigration with the language itself. And I haven’t even mentioned all the disadvantages the Gaelic Irish had under the systems of trade, commerce, Penal laws, taxes and tithes over the centuries mentioned above – or the contempt the aristocracy and the social climbers in Dublin had for the Gaels. Their fate was not their fault. It was the brutal fist of colonialism.

The Irish abandoned their language in the 19th century to survive – so that their children might live. Who wouldn’t do anything to protect their children? We cannot undo the sadness and the terrible wrongs of the past, and there is nothing good to be gained from being angry about what was done. If we want to do something constructive, we can resist colonialism and imperialism in all their forms; and we can learn and speak the wonderful Irish language as a beautiful cultural gift that transcends history, the present, and the future.

“Labhair í agus mairfidh í”, “Speak her and she will live”.

I do not use AI in the writing of my blog articles or on social media. I do use it for some research.

Please leave a comment below if you enjoyed this, or suggest a topic or interviewee for a future piece. Go raibh maith agat!

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Breise Eolas ar Oíche na Gaoithe Móire. More information on The Night of the Big Wind:

- The Night of the Big Wind. Westmeath County Council. Manus Lenihan focuses on what happened in Kilbeggan. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHckAkYBbuU

- Article from Met Éireann https://www.met.ie/cms/assets/uploads/2017/08/Jan1839_Storm.pdf

- Turtle Bunbury in the Irish Times. The calm before the Big Wind of 1839 was particularly eerie. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/the-calm-before-the-big-wind-of-1839-was-particularly-eerie-1.3257684

- RTÉ Radio 1 – The History Show – Night of the Big Wind (21/12/14) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mJeCCVmJeCc

You can help fund the work I do by supporting me on Patreon with the price of a coffee every month. Go raibh maith agat! Thank you!

#100DaysOfGaeilge – Up For A Challenge in 2026? https://irishlanguagematters.com/

Follow Me

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Great piece Derek go raibh mille maith agat.

LikeLike

Go raibh maith agat a chara!

LikeLike