A St. Patrick’s Day look at some of the themes from this week’s media relating to the Irish language.

Grianghraf: TG4

Grianghraf: Ruth Medjber

The St. Patrick’s Day Festival 2025

St. Patrick’s Day is a national celebration with enormous reach globally. This is partly due to the estimated 80 million people around the world who claim Irish descent – including one of the largest diaspora groups in the United States. The St. Patrick’s Day festival prompts considerations of ‘Irishness’ and naturally, the Irish language, Gaeilge, is an important element of that. The culmination of the annual celebration of the Irish language, Seachtain na Gaeilge, coincides with St. Patrick’s Day (events in the Irish language can be found here). This year, it is also 40 years since Raidió Fáilte started broadcasting in Irish from Belfast – comhghairdeas libh uilig! In a nod to native Irish culture, RTÉ, the national broadcaster, includes some bilingual coverage of the annual parades and news on St. Patrcik’s Day. This week, RTÉ had two current affairs programmes that focused on the Irish language, Upfront With Katie Hannon, and Prime Time.

- No Less Irish For Not Speaking Irish

I was an audience member at the RTÉ show Upfront With Katie Hannon which discussed the Irish language. There were many positive contributions made. Two people spoke about not feeling any less Irish for not speaking Irish. It’s interesting that this sentiment is frequently a response to discussion about the Irish language. I once mentioned to someone that I feel more like myself when I speak Irish, and they immediately shot back by asking did I think I was more Irish than others because I spoke Irish? I never have encountered any Irish speaker say anyone else is less Irish because they don’t speak Irish. It seems to be an emotional reaction by non-Irish-speakers triggered, for some, by the mere mention of the language, or of anyone else feeling like their identity is enhanced by being an Irish speaker – which is interesting from a psychological perspective.

It’s not just Irish speakers that love the Irish language either (and not all do). Many people express a desire to speak more Irish and a regret at not having it – I’m one. Mícheál Ó Foighil recalls his mother’s passion for the Irish language – though she wasn’t a speaker herself – as something that inspired him.

For me, and others, there is a sense of liberation and exhilaration about developing more proficiency, and a deeper relationship, with Irish. Who would argue with someone claiming they felt pride at leading their team out at Croke Park or Lansdowne Road? Would anyone object if a sportsperson said that representing Ireland enhanced their identity and their personal sense of Irishness? So, if Irish speakers sense of Irishness, or of being a Gael – or simply being someone who speaks a minoritised language in a world shaped by colonialism – is deepened by their language, they are entitled to own those feelings, and that identity. It’s not a comment on anyone else.

2. It has to be voluntary. It has to be a matter of choice.

A second argument that came up on the show was that the Irish language must be voluntary only – a matter of choice. Ironically – considering the point above – this concept frames the ‘English language only’ experience as the natural linguistic and cultural mode of existence in Ireland. It suggests that the Irish language is an unnecessary optional extra – an indulgence – at best, a choice subject at school like History, Biology or Home Economics.

Many people feel that the education system should not merely be a vehicle for creating clone workers for the economy. We hope that it will nurture our children and assist them in developing to their full potential as mature, thinking, creative human beings with agency. We expose children to art, crafts, culture and creative activities. Languages have an important role in modern living and multilingualism is the norm, globally. Kayleigh Trappe spoke on Upfront of the positive response from children to early exposure and immersion education in the Irish language. Why shouldn’t Irish children have this gift – and the ability to communicate with their fellow Irish-speaking citizens? Why should they be kept in darkness in relation to the meanings of Irish songs, stories and placenames in their original language? Why not give children the opportunity to develop a deeper sense of culture, identity and place? With all due respect to the two commenters who mentioned not feeling less Irish for not speaking Irish, it’s difficult to fully appreciate the beauty of your vista if you lack the capacity to see.

3. We are becoming more multicultural and so Irish is a hindrance.

This is another argument that came up. This is also incredibly ironic, considering the two previous points, and a particularly dangerous angle to take. Here, we see that this notion of ‘inclusivity’ deliberately excludes the Irish-speaking community. This concept of multiculturalism allows for limited acknowledgement of other cultures in a substratum beneath the Anglosphere, with one exception – Gaelic culture. It’s straight from the colonial playbook. Plan A: Get rid of Irish by insisting English be normalised in all sociocultural spheres. Plan B: If plan A fails and it is necessary to grudgingly accept cultures other than that of the Anglosphere, get rid of Irish by insisting it threatens multiculturalism (and ‘Go to hell or to Connacht’ to anyone who identifies with that community already – just act like they don’t exist).

There are many New Irish citizens who have a positive disposition to Irish culture and the Irish language. Some people from non-Irish backgrounds have become speakers of Irish. A few of these have inspired me on my own language journey. Some have pointed to “repeated attempts in the national media to use immigrants as a weapon against the Irish language, and on a lesser level, native Irish culture” (Ó Conchubhair, B. (2008). The Global Diaspora and the New Irish (Language). In Nic Pháidín, C. & Ó Cearnaigh, S. (Eds.). (2008). A New View of the Irish Language (pp. 224-248). Dublin: Cois Life.).

Michael D. Higgins’ Last St. Patrick’s Day as President

Later in the week President Michael D. Higgins made his 14th and final St. Patrick’s Day address to the Irish people. We have been so fortunate to have a principled President, passionate about the arts and culture, a person of integrity, compassion, and values, in Michael D. Higgins. In his message, he stated that “Words matter“. He is a man who has always acknowledged the importance of words, language and culture in Ireland, and indeed in the full human experience of life. Notwithstanding the challenges the Irish language faces – and there are many, especially in the Gaeltacht – I will leave the last word here to Michael D.:

“If I were to look for hope now, it would be in the Irish language, for example, among the new generation who are speaking about it. They’re actually in a time of no repression…They are able to take the complex new stuff that’s happening around them, and they’re able to see it through the prism of the Irish language.

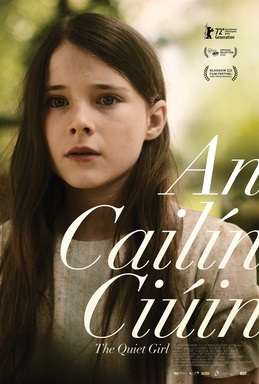

For example, it is of such significance, that you could have a film made – Arracht, is the one I’m thinking of, or An Cailín Ciúin, – and that it could go internationally, go around the world, and people will see that this is happening in a language that was in fact once forbidden, proscribed, and that in fact was saved”.

Lá Fhéile Pádraig faoi mhaise duit! Happy St. Patrick’s Day! Feel free to comment & share!

____________________

10 Irish Phrases You Can Use Today:

Conas atá tú? (Munster Irish) – ‘How are you?’

Cén chaoi a bhfuil tú? (Connacht Irish) – ‘How are you?’

Cad é mar atá tú? (Ulster Irish) – ‘How are you?’

Le do thoil – ‘please’

Go raibh maith agat – ‘thank you’

Tóg go bog é – ‘take it easy’

Sláinte – ‘health/cheers’

Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam – ‘A nation without a language is a nation without a soul’

Ádh mór ort! – ‘Good luck!’

Slán go fóill – ‘Bye for now’

What do you think? Leave a comment below?

Foghlaim Gaeilge – Learn Irish

Follow Me

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.